As attractive as it sounds, investing with a bleeding heart only leads to a bleeding portfolio. Socially responsible investing costs both you and the causes you care about a lot of money and goodwill. There are better ways to both invest your money and affect positive change in the world.

Specifically, over 10 years of investing $25,000 per year (about the max you can invest in tax-advantaged accounts), a socially responsible stock portfolio will be worth almost $30,000 less than a normal indexed stock portfolio (over 1 year of work wasted per 10 years). To make things worse, most of the money “lost” isn’t actually going to the companies doing good, nor is it leaving the companies doing bad. It’s just providing slightly better deals to all the other more opportunistic stock investors out there.

On top of that, you would need twice as much money in a socially responsible portfolio (50x average annual spending) versus a traditional one (25x average annual spending) to retire early.

Invest to make money and donate to do the most good. Don’t confuse these goals; when it comes to investing and social responsibility, half measures don’t get the job done.

Intro to Socially Responsible Investing (SRI)

A friend on Twitter recently posted an article titled, How the Gates Foundation’s Investments Are Undermining Its Own Good Works. This was the first time I had really come across the idea of socially responsible investing (not exactly the same as impact investing, but in the same family), and it really intrigued me.

The basic idea behind socially responsible investing is to make ethical investment decisions across the board. This can be defined both positively and negatively. The negative definition would be “do no evil,” while the positive definition would more narrowly require investments in companies with a proactive social or ethical mission.

For example, the negative definition might require that you divest all investments from tobacco companies, while the positive definition would require investments in companies actively working to make a positive impact in the world, such as solar panel manufacturers.

Financial Performance of SRI’s

I really wanted socially responsible investing to be equally, if not more profitable than normal index investing, but sadly it is not. One of the biggest problems with socially responsible funds is that they have high fees that really eat away your returns (it costs money to evaluate the evil or virtuousness of all those companies). On top of that, SRI funds grow slower too.

Not surprisingly, Vanguard has the lowest-cost socially responsible mutual fund out there. The interesting and potentially disheartening thing about Vanguard’s socially responsible fund, The Vanguard FTSE Social Index, however, is that it actually only seeks to mimic the return of other social indexes (it is defined negatively rather than positively). But that is what helps keep expenses low, and at a minimum, you’re still not investing in evil, although somehow Chase, Bank of America, and Citigroup are all still included in the 10 ten holdings…

But anyway, to compare the financial performance of SRI to normal investing, I looked at the total return of Vanguard’s FTSE Social Index Fund versus Vanguard’s Total Stock Market ETF. Here are the results:

As you can see value of $10,000 at the end of 10 years would be worth almost $24,000 with the total stock market ETF but only about $20,000 with the FTSE social index. The initial reaction is that $4,000 over 10 years isn’t that big of a deal, but there are two things to point out. First, that $4,000 difference is worth almost half the initial investment! Secondly, on a compound annual basis, the SRI fund returns about 2% less than the total stock market fund.

Putting this in the context of saving for retirement, remember the 4% safe withdrawal rule. The 4% safe withdrawal rate is the maximum rate that an individual can successfully withdraw from a typical portfolio without reducing their ability to withdraw an equal, inflation-adjusted amount the next year. A 4% withdrawal rate leads to a theoretically infinite portfolio.

Now here is the interesting part. If socially responsible investing returns 2% less per year than normal investing, then the new safe withdrawal rate on a SRI portfolio is 2%. In other words, you would need to save twice as much in a SRI portfolio (50 times annual spending, to be exact) as you would need to in a normal portfolio (25 times annual spending) to finance the same spending levels in retirement!

So now the real question is, are the benefits of socially responsible investing worth the additional cost of having to double your retirement savings relative to normal investing. In real terms, for a family spending $40,000 per year, is it worth saving an extra $1 million before retirement simply so you don’t have to invest in companies that do evil? My answer is no, and I’ll tell you why.

The Case Against Socially Responsible Investing

First and foremost, there are MUCH more effective ways to affect positive change (or minimize evil) in the world with a fixed amount of money. There are two sides to this argument, and I’ll start off with side a, namely that refusing to buy stock is a bad way to “punish” (or reward) companies.

Let’s talk about what stock is. Stock is simply a claim on the future earnings (profit) of a company. If a company makes $100 this year and there are 100 stocks on the market, then each stockholder is theoretically $1 richer.

Why do companies issue stock in the first place? They issue stock to raise money to grow their businesses. So, in theory, if enough people refuse to buy the stock of an evil company, the company won’t be able to raise as much money.

But here is why it doesn’t work that way: most stock market transactions are secondary transactions, meaning that you’re buying or not buying a stock from another investor, not from the company (I, an individual investor, sell to you another individual investor). The company doesn’t really see any of that money after the initial public offering.

At a maximum, a company will only issue new stock a handful of times such as their initial public offering and sometimes secondary offerings after that. Once a stock has been purchased in the initial public offering (or secondary offering), the company will have already raised their money. So by extension, refusing to invest in evil companies that have already had their public offering really isn’t punishing them at all.

Secondly, what refusing to buy evil stocks is really doing is artificially lowering the price of said evil stocks in the marketplace. This means you’re giving “less-ethical” investors (or computer algorithms working for investment banks) the chance to make even more money through the purchase of evil stocks, at your own expense to boot!

Similar to the tragedy of the commons, what this does is simply make ethical investors less and less powerful (rich) in comparison to all the other neutral and/or, dare we say, evil investors out there (and there will ALWAYS be other investors out there).

There is a possible argument to be made that if enough investors decide to boycott certain stocks, the holders of those stocks will see the value deteriorate, which could theoretically prompt shareholder activism for change. This probably wouldn’t ever happen, however, because the more people that boycott a stock and depress its value, the sweeter the deal becomes for someone to break ranks and gobble up a bunch of stocks at happy-hour prices (I repeat, there is ALWAYS another investor out there).

The flip side (b side) of the fact that “voting” with your investment dollars is a really ineffective way to punish and/or encourage positive change in the world is that there are actually some much cheaper ways to make a difference.

Let’s face it, even if voting with your dollars did work, determining the righteousness or wrongness of an entire company is a really ambiguous task. Coke, for example, does a lot of philanthropic work around the world, but they also actively market unhealthy beverages to kids and families around the world. Even if you could invest in or divest from Coke and affect change in the world, the result would be somewhat complicated.

Coke’s three priority areas, to which they contribute a combined 1% of their operating income, include economic empowerment of women, access to clean water, and well-being (active healthy living, education, and youth development). Investing in Coke because they’re actively trying to make a difference is sort of confusing two separate goals. The goal of investing is to make money (for yourself), while the goal of social good / social responsibility is to make life better (for other people).

It is mathematically impossible to maximize two variables at once, so what should be the focus? How does one balance making money and doing good? If the focus is making money then, by all means, invest where your money will grow the fastest. If it is doing good, then give that money to the place/person/organization that will do the best with it (see my recommendations). At best, socially responsible investing is an ineffective half-measure that is both costly to the investor and the causes they care about.

The Well-intentioned Parents Example

Let’s say you get a job right out of school at a publicly-traded company like Apple, and your generous and loving parents want to make sure their son or daughter is financially secure going forward, so they decide to buy a bunch of Apple stock to boost the company (and your job prospects). This is a really really indirect way of accomplishing their goal because the money doesn’t go to Apple anyway (Apple went public years ago; the money just goes to another investor).

The generous, well-intentioned parents realize their folly and decide instead to replace all their PC’s and Andriod phones with apple devices. This actually does move the needle a little bit for Apple the corporation, but because Apple is so big, it might as well be just another grain of sand on the Apple beach.

Finally, they wise up to the fact that they’re still not really helping their son/daughter have a more secure financial future by keeping demand for Apple products marginally higher than it would be otherwise. Instead of wasting money on expensive new Apple computers the next time, they buy cheap Chromebooks, and give all the extra money they would have spent directly to their child.

Maybe they add the stipulation that it needs to be invested in retirement or education or something other than beer, but ultimately, they realize this is the most effective way to achieve their goal, similar to the SRI situation described above.

The “Evil” Career Parallel

Similar to the evil stock scenario and conclusion discussed above, the big-name effective altruism outfit 80,000 Hours recommends that people go into what some would consider “evil careers” such as wall street banking instead of working for nonprofits.

Their argument is that an individual can accomplish a TON more by donating the difference of what they would make in the non-profit sector and what they make on wall street to really effective nonprofits.

Doesn’t sound too different from the SRI discussion above…

The ROI of Not Being a Socially Responsible Investor

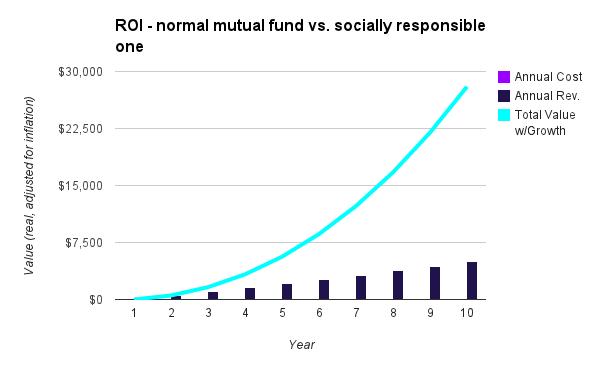

The true cost of socially responsible investing vs. normal investing is inevitably much higher than what this 10-year ROI example shows, mainly because most people’s investment horizon for retirement is much longer than 10 years, and the losses will compound over time.

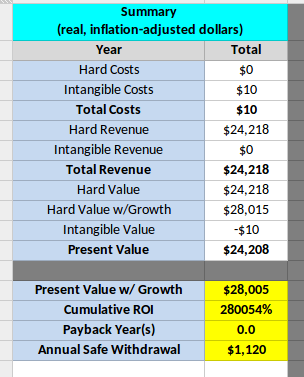

In this example, I simply compared a 4% real rate of return (my default growth assumption) to a 2% real rate of return (SRI’s return is 2% less on average according to my calculations). And I assumed that an individual is investing a total of $25,000 per year (roughly equivalent to maxing out IRA, 401k, and an employer match).

How much better would the normal investor be?

- 10-Year NPV: $28,050

- 10-Year ROI: 280,054%

- 10-Year Payback: 0.0 years

Being a normal investor and investing $25,000 per year for ten years means you will have earned almost $30,000 extra versus the socially responsible investor… good job, this is worth more than 1 year of savings (work) for you!

Now for the socially responsible crowd, take it a step further and you’ll have both made more money for yourself and made a bigger difference in the world… take a part of that $30,000 dollars, let’s say 10% ($3,000), and give it to a really effective charity for a cause you care about.

For example, in the U.S. you might give the $3,000 to the Nurse-Family Partnership or to Knowledge is Power Charter Schools. Or if you want your money to go even further towards making a difference in the world, give it to an organization like Give Directly or The Against Malaria Foundation, which saves kids’ lives at the modest cost of $3,400 per child.

I would be willing to bet my entire life savings on the fact that donating that $3,000 to a really effective charity would do significantly more good than investing the total $30,000 in socially responsible funds.

The truly generous could take it even a step further, recognizing that they would have “lost” $30,000 in the SRI case, and could choose instead to donate all $30,000 to a place like The Against Malaria Foundation, saving nearly 9 lives in the process.

Conclusion

When I first heard about SRI, I was really excited and even considered switching my entire stock portfolio over. However, after doing the research, I realized that I would only be punishing myself and the causes / people I care about. There is a better way to do things. Voting with your dollar has it’s place in life, but that place is definitely not investing.

Invest well, spend well, give well.